SPESC

Home

Introduction

The SPESC is a specification language for smart contracts, which can specify a smart contract in a similar form to real-world contracts using a natural-language-like grammar, in which the obligations and rights of parties and the transaction rules of cryptocurrencies are clearly defined. The preliminary study results demonstrated that SPESC can be easily learned and understood by both IT and non-IT users and thus has greater potential to facilitate collaborative smart contract development.

Background

Cryptocurrencies

Decentralized cryptocurrencies have rapidly gained in popularity since Bitcoin was introduced. Conceptually, a decentralized cryptocurrency system, which is administered without relying on any trusted parties, maintains and secures some shared data that are stored using blockchains. As a data structure, a blockchain is an immutable ordered list of blocks. Each block consists of many transaction records and a hash of the previous block. The data stored in the blockchain cannot be deleted or altered; otherwise, the hashes will be invalidated.

Blockchains

A block chain is a simple cryptographically secured data structure that takes a number of records and puts them in a block (like collating them in a single sheet). Each block is then chained to the next block, using a cryptographic hash. This allows the block chain to be used like a public ledger, which can be shared and corroborated by anyone, without having to worry that the stored records can be changed. Therefore, Blockchain is the term that is used to describe this distributed and decentralized ledger system that is spread across multiple sites, countries or institutions.

Smart Contract

A prominent and promising use for blockchains is to enable smart contracts. Technically, a smart contract is a program that is deployed and running on blockchains. Smart contracts have been used to realize various applications and operations (such as financial instruments, product traceability service, and self-enforcing or autonomous governance applications).

Language of Smart Contract

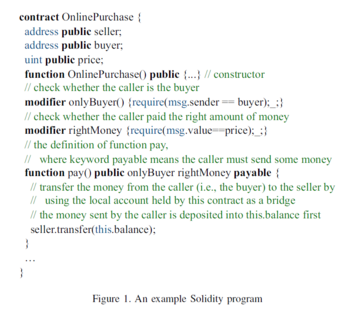

A smart contract is encoded using smart contract programming languages, such as the script language of Bitcoin and Solidity of Ethereum. For instance, Fig. 1 shows a code snippet of a smart contract that is written in Solidity. The code snippet demonstrates a function that is callable by a buyer to pay a seller a certain amount of cryptocurrencies.

The Reason We Propose SPESC

Although a smart contract is usually viewed as an online program from the perspective of information technology, it is actually an interdisciplinary concept that also concerns (but is not limited to) business/finance and contract law. From the point of view of business and finance, a smart contract specifies how transactions and payments are executed among different accounts. From the point of view of contract law, a contract is an agreement between parties consisting of mutual commitments; and, a smart contract is a contract in which the commitment fulfillment is performed automatically.

Due to its interdisciplinary nature, a smart contract may be proposed, designed and implemented collaboratively by many experts, such as software and information security engineers, business experts, bank managers, and lawyers, who come from different domains. A crucial issue during smart contract development is to enable domain experts to understand, discuss and specify the contract collaboratively. Existing smart contract languages, such as Solidity and Hawk, are primarily defined from an IT perspective. The smart contracts that are encoded using these languages (as illustrated in Fig. 1)may not be readable to the practitioners outside of the IT industry.

SPESC is intended to be used to define the specification of a smart contract (rather than its implementation) for the purpose of collaborative design. In SPESC, a smart contract is regarded as a composition of information technology, contract law, and business/finance transaction. First, SPESC enables us to specify a smart contract in a similar form to a real-world contract. An SPESC specification consists of the descriptions of parties (i.e., the roles that participate in the contract) and a set of terms (i.e., the obligations and rights of each party, and the conditions when the terms should hold). Second, for each term, SPESC also enables us to describe how the balances of the parties’ accounts should change when this term holds. Finally, SPESC enables us to derive a program skeleton (or a program interface) in accordance with the contract terms and the account balance changing rules associated with each term. Such program skeletons can be further completed by developers to implement an executable smart contract.

SPESC

A smart contract is a program that owns not only IT attributes but also financial and legal attributes. Smart contract development requires the close cooperation of experts from related domains. The goal of SPESC is to establish an abstraction layer atop concrete implementations of smart contracts to facilitate the collaboration among experts from different domains. In SPESC, a smart contract is viewed as a cross-disciplinary artifact and is specified from three perspectives, i.e., programming, business/finance transactions and contract law.

The rest of this section will use a simple Purchase contract to illustrate SPESC. This simple contract must be signed by a buyer and a seller. When the contract is signed, the price of the product must be specified. The buyer must pay within three days after the contract is signed, unless the buyer cancels the contract. The payment is frozen rather than transferred to the seller directly. The buyer can cancel this contract before payment. The seller must post the product within five days after the payment. The buyer must acknowledge the receipt of the product within ten days after the product was posted. While the receipt of the product is acknowledged, the payment will be transferred to the seller. If the buyer did not acknowledge the receipt of the product in time, then the seller can also collect the payment.

General Structure

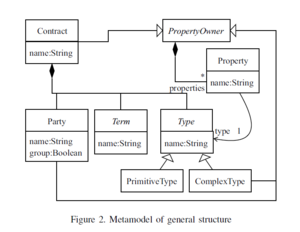

In SPESC, a contract consists of parties, contract properties, terms and data type definitions. The metamodel of the overall structure of SPESC is presented in the following code.

Contract in this code snippet represents a smart contract under development. Party denotes a role who participates in the contract and interacts with others. Term specifies a certain obligation or right that is associated with a party. The detailed definitions of Party and Term will be presented later.

A contract in SPESC may also own some contract properties. Property denotes a static field of a certain data type. Contract properties can be used to specify the necessary properties of the object of the contract, such as the amount and the price of the goods to be sold.

As a program specification, an SPESC contract must also precisely define the data types that have occurred (in a realworld contract, the data type may be determined by common sense). SPESC enables us to explicitly define data types using Type, which has two concrete subclasses, namely, PrimitiveType and ComplexType. The meanings of PrimitiveType and ComplexType are consistent with conventional programming languages. In our tool support, we have provided some predefined types, such as String and Money.

The following code snippet shows the general structure of the contract Purchase that is written in the concrete syntax of SPESC. Keywords contract, party, term and type indicate the corresponding concepts.

- !SPESC

contract Purchase {

party Seller {/* details of Seller */}

party Buyer {/* details of Buyer */}

info : ProductInfo // contract property

term No1 : … /* details of Term */

term No2 : …

…/* other Terms */

type ProductInfo {

price : Money,

model : String

}

}

Parties and Terms

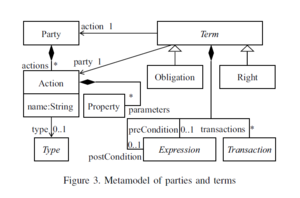

Parties and terms are essential components of a realworld contract. The SPESC metamodel that concerns parties and terms is presented in Fig. 3

In SPESC, a Party is specified by a name that is used as an identifier in the rest of the contract, some party properties (i.e., the information that must be recorded on the blockchains) and a set of Actions. Each Action represents a certain act a party may or must perform. An Action is declared (and will be implemented) as a function in a smart contract program. In a real-world contract, a party can generally do anything that is not prohibited; however, in SPESC, we assume that a party can only perform an action/function that is declared.

By default, a Party is a user of a smart contract system. SPESC also supports multiple users playing the same role by assigning the attribute group of Party true.

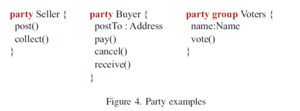

Fig. 4 shows three party declarations. The first two examples show how the parties Buyer and Seller are defined in the concrete syntax of SPESC. In the examples, Buyer can perform three Actions, namely, pay (i.e., pay the order), cancel (i.e., cancel the contract) and receive (i.e., acknowledge receipt of the goods), and Seller can perform two Actions, namely, post (i.e., post the goods) and collect (i.e., collect the money). The third example demonstrates a group party Voters, which at runtime can be played by multiple users.

After declaring an Action for a Party, we must specify when the Action must or may be performed by this Party by using contract Terms. In Fig. 3, a Term refers to a Party and an Action of this Party and is associated with pre/postconditions (specified by Expressions). Term has two subclasses, namely, Obligation and Right. An Obligation term defines that the referred Party must conduct the Action under a certain precondition. A Right term defines that the Party may conduct the Action under a specified precondition. When the term condition does not hold at runtime, we assume that the Party cannot conduct the Action.

SPESC regards transactions as the core of smart contracts. SPESC provides a way of specifying the cryptocurrency transactions for each Term. In Fig. 3, Term may also be associated with a set of Transactions. The details of Expression and Transaction will be introduced later.

For greater comprehensibility, SPESC employs a natural-language-like concrete syntax to specify contract terms. The concrete syntax for Terms is defined as follows in EBNF, where the concepts defined in the metamodel of SPESC are displayed in italics and keywords are displayed in bold type.

term name : party (mustjmay) action

(when preCondition)?

(while transactions+)?

(where postCondition)?

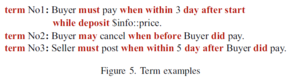

A Term owns a preCondition, which specifies the condition under which the term must/may be fulfilled, and a postCondition, which specifies the condition that must hold after the term is fulfilled. The following examples show three terms (i.e., No1 to No3). Term No1 is an Obligation term. It specifies that the Party Buyer must perform the Action pay within three days after the contract starts and that Buyer must deposit an amount of cryptocurrencies as specified by price of the contract property info. Term No2 is a Right term. It specifies that the Party Buyer may perform the Action cancel (only) before he pays. Term No3 is also an Obligation term. It states that the Seller must perform the Action post within three days after the Buyer pays.

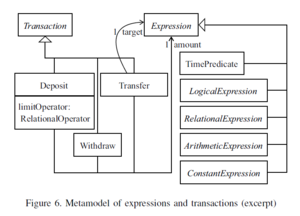

Expressions

SPESC supports various expressions to specify term conditions, such as time predicates, logical expressions, relational expressions, arithmetic expressions and constant expressions. Fig. 6 shows the metamodel of expressions and transactions in SPESC. Due to space limitations, Fig. 6 only shows parts of the complete metamodel. Basic expressions, which are supported in SPESC, are summarized as follows. Their detailed definitions are omitted in this paper.

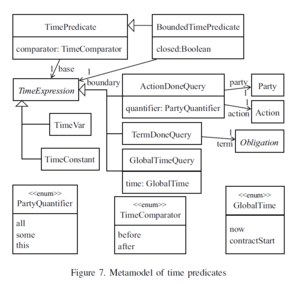

LogicalExpressions, such as and, or, not and implies. RelationalExpressions, such as >, >=, <, <=, =, !=, and belongsTo. ArithmeticExpressions, such as +, -, * and =. ConstantExpressions, such as 0 and true. In a real-world contract, the obligations and rights of parties are usually defined under certain temporal conditions. For example, a buyer must pay within three days after the contract is signed. We assume that the temporal condition is essential for a smart contract specification. SPESC supports TimePredicate to define temporal conditions. The definition of TimePredicate is presented in Fig. 7.

TimePredicate checks the relation between the current date/time and the base time point. If the comparator of a TimePredicate is before, then this TimePredicate checks whether the current time is earlier than the specified base time point (defined as a TimeExpression); otherwise, this TimePredicate checks whether the current time is later than the base time point. Its concrete syntax is defined as follows.

(before|after) base before b is equivalent to current time <= b, and after b is equivalent to current time >= b

TimeExpression is used to specify a time point. It has five subclasses, namely, TimeVar, TimeConst, ActionDoneQuery, TermDoneQuery and GlobalTimeQuery. TimeVar refers to a variable that denotes a date/time. TimeConst denotes a time constant, such as 5 day and 1 hour. GlobalQuery can return the current date/time and the creation time of this contract. ActionDoneQuery denotes the time point when a certain action is conducted by a party. Its syntax is as follows.

(all|some|this)? party did action If the party did not perform the action, then ActionDoneQuery returns 丄. 丄 denotes the unsolved time. Any solved time value is earlier than 丄.

ActionDoneQuery may contain a quantifier (i.e., all, some and this) when the party denotes a group. Consider the previous example of the party group Voters (Fig. 4) who can vote and delegate others to vote. Assume that there are n Voters in total and that ith voter voted at ti.

Quantifier all means that ActionDoneQuery returns the time when the last member in the party performs the action. For instance, all V oters did vote returns max(t1; …; tn). Quantifier some means that ActionDoneQuery returns the time when the first member in the party performs the action. For instance, some V oters did vote returns min(t1; …; tn). Quantifier this means that ActionDoneQuery returns the time when the user referred by the contract Term performs the action. For example, the following term VoteOnce prescribes that a voter can only vote once. term VoteOnce: Voters may vote

when before this Voters did vote.

For a user who belongs to Voters, we check his/her voting time when evaluating the term VoteOnce.

TermDoneQuery is similar to ActionDoneQuery. It denotes the time point when an Obligation term is fulfilled.Assume that the queried Obligation term states that party p must conduct an action o. A TermDoneQuery about this term is equivalent to an ActionDoneQuery, i.e., all p did o.

BoundedTimePredicate extends TimePredicate by an extra time boundary. The boundary may be a closed boundary or an open boundary. Its concrete syntax is as follows.

(within)? boundary (before|after) base There are four basic forms of BoundedTimePredicate. Their semantics are listed as follows.

within b before t: It is equivalent to check t - b <= current time <= t. For example, within 3 day before Buyer did pay. b before t: It is equivalent to check current time <= t-b. For example, 2 day before Guest did arrive. within b after t: It is equivalent to check t <= current time <= t + b. b after t: It is equivalent to check t + b <= current time. The expressions supported by SPESC are not Turing complete. It is possible that some complex conditions cannot be encoded into SPESC currently. The major reason is that SPESC is a specification language for collaborative development rather than an implementation language. SPESC is expected to be understandable by non-IT experts. Hence, we made a trade-off between the completeness/expressive power and the learnability/understandability of SPESC. As a future work, we plan to enhance the expressive power of SPESC while keeping its learnability.

Transactions

On a cryptocurrency platform, every user has an account (or a wallet) that holds some cryptocurrencies; every smart contract program also has an account. Users may transfer some cryptocurrencies from their accounts to a smart contract’s account when they are interacting with this smart contract. Users may also ask a smart contract to transfer some cryptocurrencies from its account to other accounts.

To model the transaction amount accounts, Fig. 6 also defines the concept of Transaction. SPESC currently supports three types of Transaction, namely, Deposit, Withdraw and Transfer. The concrete syntax of the three transaction operations is listed as follows.

deposit (= | > | >= | < | <=)? $amount withdraw $amount transfer $amount to target

Deposit means that a user must put some cryptocurrencies into the account of the smart contract he/she is interacting with. The limitOperator, which is expected to be =, <, <=, > or >=, indicates whether the cryptocurrencies to be saved should be equal to or less/greater than the specified amount. If the limitOperator is missing in concrete syntax, then it is regarded as =. Withdraw means that a user will get a certain amount of cryptocurrencies from the account of thesmart contract he/she is interacting with. Transfer means that the smart contract will give the target some cryptocurrencies as specified by amount. All amounts of cryptocurrencies are specified by an Expression; target of Transfer is expected to reference a Party.

Recall the example Purchase contract. According to the contract description presented at the beginning of Section 3, Buyer is expected to pay for the goods when he/she performs the action pay. The money he/she pays will be frozen by the smart contract. Hence, in Fig. 5, term No1 contains a Deposit operation to ask the Buyer to transfer the goods price to the smart contract’s account. The contract Purchase also states that Buyer must receive the goods within 15 days after they are mailed, and must unfreeze and transfer the money to Seller; otherwise, Seller can collect the money. We realize this requirement by defining the following two terms.

term No4: Buyer must receive

when within 15 day after Seller did post while transfer $info::price to Seller.

term No5: Seller may collect when 15 day after Seller did post

while withdraw $info::price.